Co-temporality and aftermath epistemology in the wake of the 2015 Nepal earthquakes, by Uma Pradhan

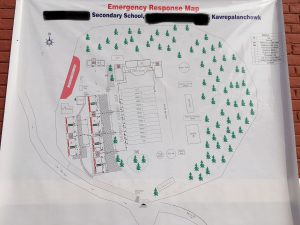

‘I can never forget how I felt during the earthquake. The ground was constantly shaking, and I thought our time of living in houses, studying in proper classrooms was over. We lived in tents for many days’, a student in a newly reconstructed school in Nepal’s Kavrepalanchowk district told me. I was conducting a study on school reconstruction projects in post-earthquake Nepal. This school had been completed with financial support from the Asian Development Bank under the coordination of the Nepal Government’s District Level Project Implementation Unit (DLPIU). One of the officials coordinating this programme offered his thoughts: ‘This earthquake has frightened many people. We find that people are more cautious now. They understand the importance of earthquake resistant building codes and other safety protocols.’ These new school reconstruction frameworks were launched under the Building Back Better programme of the National Reconstruction Authority, with an estimated budget of US$ 397.1 million for the construction of 31,488 schools.

Many people I met during my fieldwork recalled their vivid memories of the 2015 earthquake and how this event shaped their emotions about their material surroundings. The earthquake also moulded people’s perspectives on upcoming plans. The earthquake was not just an objective event in the past. It was also a subjective experience that was felt in the present, with sensory details, imagery and emotions that very much shaped perspectives on the future. This subjective experience fashioned many of the reconstruction plans and activities, which in turn were oriented towards a future in which there remained the possibility of another disaster which would need to be mitigated. The aftermath of a disaster was, therefore, a time that called for a ‘reworking of the present normality as a time of precaution, pre-emption, and preparedness’ (Anderson 2010).

Past, present and future thus combine within the event of a disaster. This co-temporality opens up spaces for seemingly disparate elements to coalesce and generate a variety of post-disaster discourses and practices. Nepal’s Post Disaster Recovery Assessment for the education sector envisages ‘safe learning environments and comprehensive school safety’ where ‘disaster risk reduction is mainstreamed in the education sector through strengthened disaster management and resilience among communities’ (GoN 2016: 10). All new school designs now need to be in line with ‘build back better’ principles in terms of earthquake resilience and to be based on proven technical know-how. The key features of these buildings include child friendly facilities, WASH facilities, and where possible, sustainability features such as solar energy and rainwater harvesting.

Such expectations of material transformation are accompanied by training and capacity building on Disaster Risk Reduction. The Government of Nepal plans to ‘give education a central role in natural disaster management by teaching children, and through them their parents and communities, about risk reduction and disaster preparedness’ (GoN 2016b). The School Sector Development Plan has advanced the concept of safe schools which is bolstered by the three pillars of the comprehensive school safety framework: (i) safe infrastructure; (ii) strengthened disaster risk management; and (iii) strengthened resilience in communities and among stakeholders (GoN 2016a: viii). Through these programmes, the Nepali state plans not only to rebuild the damaged schools, but also to change public perceptions of state education by transforming some high performing government schools into ‘model’ schools.

Post-disaster epistemologies thus tie up the past, present, and future in ‘complex knots’ (Haraway, 1994) of a variety of actors, ideas, and actions that begin to be constituted as objects in themselves: Disaster Management Plans, Building Codes, DRR trainings, etc. Such attempts to respond to disaster are shaped by past experiences and eventually shape plans to prevent and respond to a potential future disaster. While these plans are obviously rooted in existing interests, priorities, and competencies, they also play an important role in defining preparations for any future eventuality. Post-crisis reconstruction therefore serves as an analytical space of possibilities where old structures break down and produce alternatives that are often unforeseen at the outset.

As post-disaster objects begin to take shape, new ideas—whether they are about risk measurement, intervention mitigation, safer spaces, good practices and so on—also begin to shift and change in relation to one another. New plans are updated with new learnings, in which past, present, and future begin to coalesce again in different ways. Therefore, a close attention to the justifications for reconstruction programmes—what scholars have called ‘aftermath epistemology’—may provide insights into the ways in which a post-disaster period can be utilised to construct new socio-political agendas and generate visions for collective futures (Simpson, 2001). In such contexts, hyper-visible infrastructure projects can also function as spaces to explore the invisible dimensions of infrastructures, where the rules governing the space of everyday life are also constructed. The challenge facing those of us who hope to understand these shifting meanings is to find a way to trace the mechanisms that shape the ways in which we think and act in a post-disaster context.

Reference

Anderson, B. 2010. ‘Preemption, precaution, preparedness: anticipatory action and future geographies’ Progress in Human Geography 34: 777–798

Government of Nepal (GoN) 2016a. School Sector Development Programme 2016 – 2023. Kathmandu: Ministry of Education.

Government of Nepal (GoN) 2016. Nepal Earthquake – Post Disaster Needs Assessment: Sectoral Reports. Kathmandu: Nepal Reconstruction Authority.

Haraway, D. 1994. ‘A game of cat’s cradle: science studies, feminist theory, cultural studies’ Configurations 2: 59–71.

Simpson, E. 2001. The Political Biography of an Earthquake: Aftermath and Amnesia in Gujarat. London: Hurst & Co. Publishers.