A Visit to the Epicentre, by Michael Hutt and Khem Shreesh

Michael Hutt and Khem Shreesh visited the villages of Barpak and Laprak in Gorkha district on 6-9 March 2019. Barpak, located on a broad shelf of land at 1900m, is regarded as the epicentre of the magnitude 7.8 earthquake of 25 April 2015. Laprak, located approximately 10 kilometres to the north of Barpak, stands on old landslides on the lower slopes of a northfacing hillside at 2100m. The majority of Barpak’s population of 4985 people are Ghales and Gurungs, and the majority of Laprak’s 2161 people are Gurungs (figures from the 2011 Census). Each village also has a small Dalit population. Both villages have a strong tradition of service in the British and Indian armies, and many of their young men are working in Gulf countries and elsewhere overseas. Many youths from Laprak are engaged in the tourism industry as trekking guides and porters.

Both of these villages were almost totally destroyed by the 2015 earthquake. However, their experience of its aftermath has been radically different. The majority of Barpak’s 1300 houses have been or are being reconstructed. Most homeowners have accessed the financial subsidies disbursed by the National Reconstruction Authority, and 26 houses owned by British Army welfare pensioners have been rebuilt with funds provided by the Gurkha Welfare Trust. Several locals pointed out to us that while in pre-earthquake Barpak houses were all of much the same size, in reconstructed Barpak there are now small houses and large houses, making disparities of wealth more clearly apparent. New school buildings are being built with funding from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and work has begun on the creation of a national earthquake memorial on 217 ropanis of land above the village. Built to a circular design, this structure will have a large clock whose hands have stopped at 11.56, fourteen pillars to represent the fourteen districts that were most seriously affected by the earthquake, and the inscribed names of the 9200 people who died all across Nepal.

Things are very different in Laprak. A huge landslide occurred there in July 1999 and the precariousness of its location has now been underscored by the devastation of 2015. A new ‘integrated settlement’ (ekitrit basti) of 573 houses is therefore being created, to which the Laprakis are expected to relocate when its construction has been completed. Much of the funding for the building of this new village is being provided by the Non-Resident Nepali Association (NRNA), which raised a total of some 420 million rupees (nearly £3 million) from its worldwide membership in the aftermath of the earthquake. Having used some of this money in support of relief operations, the NRNA decided to use the rest (approximately 350 million rupees) on a major project, and to focus on the needs of the people located closest to the epicentre.

After the earthquake struck, many Laprakis fled up the hillside to an area of comparatively level ground known as Gupsi Pakha, some 600m above their destroyed village, and lived there for months (some for years) in temporary shelters. The land at Gupsi Pakha was owned by the Nepal Government, and the agreement to build a new settlement there was finalised between the National Reconstruction Authority, the Ministry for Urban Development and the NRNA on the first anniversary of the earthquake. The NRNA took financial responsibility for housing construction, for which it allocated Rs 250,000 per beneficiary household. A number of other INGOs have also become involved in the project: CARE Nepal, for instance, is organising the water supply system, while the Lutheran World Federation is constructing the roads. The new village will have a health clinic and a new school is already in operation lower down the hillside to the north.

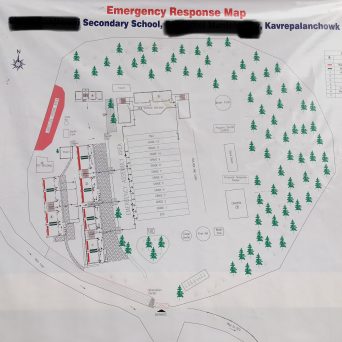

We were shown around the Gupsi Pakha site by the Nepal Army officer in charge of operations and the NRNA’s Dil Prasad Gurung, the site overseer. Although 12 Baisakh 2076, the fourth anniversary of the earthquake, had been set as the target date for completion, we were told that only 62% of the work had been completed as of one week earlier, so the project seems likely to overrun. Each of the 573 houses is identical, with two ground floor rooms, an attic that runs the length of the house, and an outside toilet. The original design for the houses, which used bamboo for an upper course of the wall and the attic floor, had been ‘cancelled’, and timber was now being used instead. The original plan to use zinc sheeting for the roofs had also been rejected due to concerns about excessive condensation, and this was being replaced with UPVC roofing. The houses of the new village are arranged on a grid pattern, and the village is laid out in sixteen blocks. All of the bricks were being manufactured on site, while the lighter concrete blocks that are being used for the upper sections of the walls were being transported from Chitwan. The only motorable route to both new and old villages is an unmetalled road from Barpak, over the 2800m Mamche pass, which was constructed after the earthquake.

On the day of our visit to Gupsi Pakha, 185 Nepal Army personnel and 120 civilians were working on the site. The soldiers were under the command of the Rana Singh Dal Battalion based at Gorkha, but skilled tradesmen had also been seconded to the project from 52 other Nepal Army units. The Nepal Army had been contracted to construct the brick, timber and steel frame of each house, with other contractors responsible for the roofing and painting. At an early stage of the project, Laprakis carried up all of the wood, rocks and aggregates as a labour contribution. Every Lapraki household that was deemed eligible by the National Reconstruction Authority [NRA] was allocated one of the new houses through a lottery process in 2016. This allocation was apparently carried out without reference to the settlement structure of the old village, in which caste and ethnicity must have played a role.

We discovered when we visited the old village that most of its houses had been rebuilt or were being rebuilt. In such a brief visit we were not able to establish how much of this work, if any, had been funded through reconstruction grants from the NRA, or the extent to which Laprakis had drawn upon their own resources and/or taken out loans. Some had reused materials from collapsed houses, and it seems likely that many did not rebuild in accordance with the NRA’s earthquake-resistant building codes.

All of the Laprakis we spoke to – a random sample of about twenty people over the course of only a few hours, admittedly – were ambivalent about the prospect of relocating to the new village. Some said that it would be too cold due to its higher altitude (drifts of snow still lay on the ground on the day of our visit) and that older people would not be able to live there. A few thought they might relocate temporarily to the new village during the rainy season, when the risk of landslides around the old village is greatest. Almost all pointed out that their farmland and fields were located around and below the old village. They would not be able to grow any crops at Gupsi Pakha, they said, and maintaining their fields would involve daily journeys up and down the steep hill slope.

Before the earthquake, Laprak had the reputation of being a tightly-knit, self-sufficient community with a high degree of ethnic and cultural cohesiveness: Gurung is clearly still the dominant language there. One cannot help but wonder what the future holds for this community. Those whom we asked confirmed that they were consulted on the project, but several said that at that time they were still too frightened by the earthquake to think through its implications clearly. If many of the people of Laprak decide not to relocate to the new village at Gupsi Pakha, they will remain at risk of further landslides in the old village, whether these are due to monsoon rains or earth tremors. If they do relocate, it may be difficult for some to continue to sustain themselves through agriculture; other kinds of livelihood may have to be sought, which would alter their way of life quite radically.

We hope that other researchers may be encouraged to visit Laprak after the Gupsi Pakha settlement has been completed to explore these matters in greater depth.

We wish to record our thanks to Dr Hemanta Dabadi (CEO, NRNA), Roshan Kumar BK (Chairman, Barpak-Sulikot Ward), Dil Prasad Gurung (NRNA), and the army officer in charge at Gupsi Pakha for their advice and guidance.

Photos:

- General view of the Gupsi Pakha construction site (Khem Shreesh)

- Houses under construction at Gupsi Pakha (Michael Hutt)

- Gupsi Pakha model house (Michael Hutt)

- Laprak village (Khem Shreesh)